Alliance for Watershed Education of the Delaware River

Alliance for Watershed Education of the Delaware River

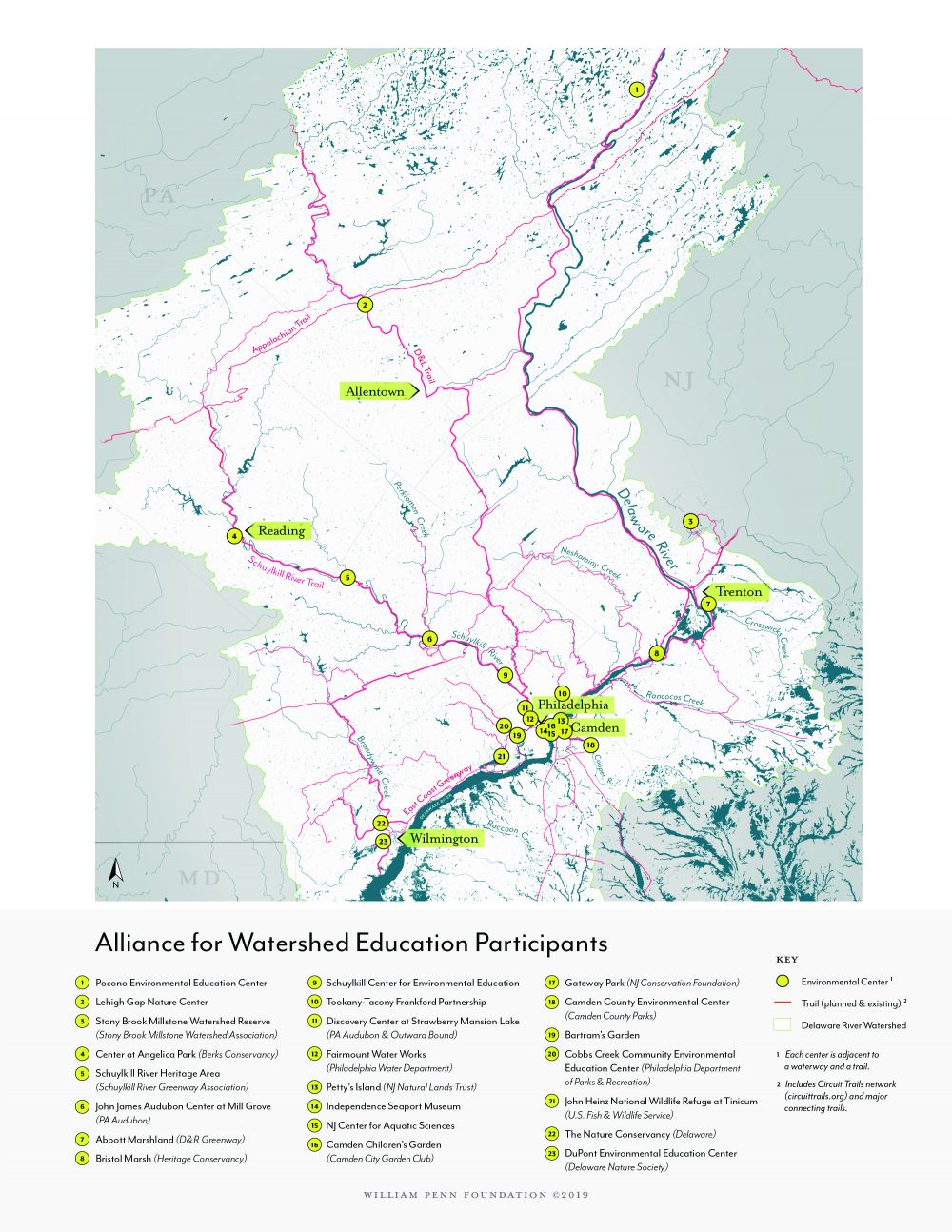

At the William Penn Foundation, we believe that healthy watersheds foster healthy communities. A number of factors are necessary for a watershed to remain healthy over the long term; among them, equitable public access to and engagement with waterways to expand the chorus of people who raise their voices in support of clean water. To help deepen engagement in the watershed, we provided funding to establish the Alliance for Watershed Education (“Alliance”) in 2015. The Alliance unifies the efforts of 23 environmental education centers in their work to build public will to protect the Delaware River watershed, the source of drinking water for more than 13 million people in four states. By collaborating and learning together, the centers are collectively building a larger and more inclusive constituency for clean water. To date, we have committed more than $11 million to support the Alliance.

The Challenge

Since the 1972 passage of the federal Clean Water Act, point-source pollution has declined dramatically in rivers across the country, including the Delaware River and its tributaries. Impaired waterways in the urban core of the Delaware River watershed in particular have made a remarkable comeback. However, the legacy of this pollution lingers and has left many communities—primarily communities of color— disconnected from the waterfront. On top of that, diffuse nonpoint sources of pollution are on the rise and threaten clean water. We noticed that the environmental centers we were funding over the decades were addressing many of these issues locally, but we hypothesized that they could be even more effective if they worked together and put their work into the larger watershed context. The existing challenges we took into account when conceptualizing the Alliance are described in further detail below.

Toward the end of the 19th century, significant reaches of the Delaware River and its largest tributaries became busy industrial hubs, including major ports in Philadelphia and Camden. For more than a century, these urban waters were heavily impaired by industrial pollution and raw sewage, rendering them unfit for human contact. As the industrial landscape changed and manufacturing and shipbuilding departed in the second half of the 20th century, the vacant, contaminated infrastructure left behind continued to prevent communities from accessing the water’s edge. At the same time, substantial public and private investment in pollution control resulted in dramatically improved water quality in those same waterways, although access to them was significantly restricted.

In the context of our goal to connect people with local waterways, it is important to note that a key challenge is the fact that communities of color have been largely left out of the conservation movement, often as a result of discriminatory policies and practices. People of color are underrepresented in leadership, staff, and volunteer roles at environmental nonprofits, government agencies, and foundations (Green 2.0), as well as in the outdoors (The George Wright Forum). Communities of color as well as lower income neighborhoods are also more likely to experience the negative effects of water pollution and other environmental injustices than white and higher income areas (A Twenty-First Century U.S. Water Policy). We believe that the diversity of the residents in the Delaware River watershed should be reflected in the movement to protect it, and that the movement would be strengthened as a result.

Today, many waterways are becoming increasingly fishable and swimmable. However, nonpoint sources of pollution are a growing threat to clean water including development in headwater forests, runoff from agricultural fields, and stormwater, which we are addressing through other elements of our Watershed Protection program. Because these nonpoint sources of pollution are principally the result of how we collectively use our land, people have the power to make small changes in their own lives and to advocate for larger changes within their local municipalities and states. Environmental education centers are poised to educate, inform, and motivate people into personal action.

The Opportunity

People protect what they love. Even a single engaging experience in the outdoors can create a stronger personal connection to the environment, and people who develop this affinity through ongoing experiences over time may be more likely to develop a stronger connection with nature, positive environmental values, and sustained pro-environmental behaviors (The Concept of Dosage in Environmental and Wilderness Education).

Ensuring adequate and equitable access to the outdoors —and in our case, to waterways—is a crucial first step. Creating more points of entry to rivers and streams, including boat docks and waterfront trails, makes the water more inviting, and provides people with more opportunity to experience it.

In addition to access, we believe it is important to provide opportunities for all people to actively engage with rivers and streams. In this watershed, dozens of environmental centers in rural areas, suburbs, and the urban core of Philadelphia and Camden (which has been most affected by pollution over the years) foster such engagement through high-quality programs and experiences. Together, they play an essential role in educating more than 180,000 people annually about threats to clean water while sharing the importance of the resource through on-water experiences, drawing on their deep understanding of their own local rivers and streams. In this work, the centers recognize the need for their spaces and programs to be welcoming and accessible to audiences of all cultures, backgrounds and abilities. Many are located in cities across the watershed not historically served by environmental organizations, and have prioritized growing a more inclusive constituency.

Early on, we saw evidence that there was desire among some of these centers to collaborate – and we set out to build on that momentum. Through our prior support of many environmental centers in the region, it became apparent that most of those centers use nearby rivers and waterside trails for experiential programming. Because of these and other similarities, subsets of centers were already beginning to collaborate – which we perceived as evidence that something larger could take root. Yet there is also a wide range of differences among them; each organization has its own strengths, opportunities for growth, and program types. Some centers are well-established, while others are just starting out. We believed that, when brought together in a network model, this range of experience would be beneficial for creating rich learning opportunities, and sharing effective practices and resources, including around equity and authentic community engagement. We also believed that a network would expand strong watershed education – with the potential to build an environmental ethic among participants in the long term – to a larger scale.

Finally, we thought that demonstrating that thousands of people across the watershed access and benefit from these high-quality programs could garner more attention, funding, and support.

Our Approach

With an understanding of capacity in the field and the significant opportunity to bring centers within this watershed together, we set the process in motion of creating a network among them. Our vision for this network was to generate long-term public will to protect clean water among communities, ensure equitable access to the important environmental experiences offered by the centers, and for the centers to join their efforts to increase momentum.

In 2015, we invited a group of centers across Delaware, New Jersey and Pennsylvania to establish the Alliance for Watershed Education of the Delaware River. We already supported many of these centers independently, and continue to do so to sustain their capacity to provide engaging environmental learning experiences. Over the past five years, the centers have formed a strong coalition with joint programs, opportunities for sharing and learning, and a structure to collect data about participants’ attitudes toward the environment.

After two years of site visits, a participatory planning process, and piloting early ideas, the Foundation made an investment of $4.5 million in 2016 to support the Alliance for two and a half more years. This investment was made through grants to:

- National Wildlife Federation (NWF), to manage collaboration across the Alliance;

- Audubon Pennsylvania, to develop and implement a fellowship program;

- Independence Seaport Museum, to organize coordinated communications across the network; and

- Wildlife Information Center, to help centers further deepen learning across the network.

During this period, an advisory committee provided general guidance on the network’s goals and strategy, while NWF and consultants added vision and coordination support.

In April 2019, we awarded a $6 million grant to NWF to support the Alliance’s work for three more years. The process to develop the grant required deep involvement and collaboration on the part of the Alliance, including goal-setting, budget decisions, and program refinement. This was only possible due to the trust that they developed with each other over time. Under the 2019 grant, the steering committee has more decision-making authority, including considering recommendations from nine working groups (funded through NWF) that focus on advancing Alliance goals around specific topics, including special events and programs, network development, communications, inclusion, and more.

Progress to Date

In a relatively short time, the centers have developed shared goals that drive their work. They have focused energy on developing shared programs and institutionalizing learning that will benefit all members, effectively expanding opportunities for environmental education across the watershed. See below for their shared goals and specific examples of programs they’ve developed.

With 23 organizations comprising the Alliance, identifying and agreeing upon shared goals for the network was a major feat. These goals drive the Alliance’s programs and activities, and the group is currently developing measures to track progress against them.

By Spring 2022, the Alliance will challenge and equip members to:

- Create a larger and more inclusive constituency of people engaged at centers and their waterways.

- Increase and enhance knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions.

- Collaborate and learn from each other to deliver high-quality and inclusive watershed education programs.

To address the need for more focus and action on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the environmental field, the Alliance developed a goal to grow a more inclusive constituency connected and committed to ensuring protection of the watershed. Fourteen centers are located in Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington, where the majority of people are of color, some of whom may not have historically felt welcome at their local Alliance center. A portion of our funding supports training to help build centers’ capacity to effectively engage on this issue. The Alliance has also formed a working group to support a strategy around diversity, equity, inclusion, and access.

Each summer, the Alliance for Watershed Education employs a cohort of Delaware River Fellows. Under this program each center hosts one young adult from a nearby community, often one that has historically been underrepresented at their center. The fellowship program adds staff capacity to each of the centers while also engaging a young adult who wants to turn their interest in the environment into hands-on experience, and potentially a career. Along the way, they develop an environmental ethic that is intended to last beyond the program.

Projects conducted by the fellows often focus on providing education, creative programs, and community outreach, with a goal of growing and diversifying interest in each center. Several fellows have been hired for full-time positions by their respective host centers, and others have decided to return for a second year of the fellowship.

To date, our funding has supported three cohorts and more than 80 individual fellows. At least 10 fellows have been hired for full- or part-time work by centers in the Alliance.

Each fall, the Alliance hosts “River Days,” its signature month-long, watershed-wide event series for the public. River Days aims to elevate the importance of experiential environmental programming, increase watershed knowledge, and promote individual and collective action to protect clean water. River Days engages, on average, roughly 10,000 individuals across the watershed each year in stewardship activities. Events range from on-water paddles and community cleanups to nature photography workshops and cycling events. Over time, centers have begun to host these events together, garnering more visibility for their programs.

What We’re Learning

We established the Alliance with a broad concept in mind: to foster relationships among centers, with the potential to leverage this network to raise the visibility of the Delaware River watershed. The 23 founding members have actively shaped this concept into a reality. During the development of the network, it was imperative for us as a funder to adapt based on the centers’ feedback and needs. We learned that it is important to be patient, and to give the network time to grow. We have seen early relationship-building turn into trust, yielding new collaborations, programs, and learning.

And yet, there is still room for improvement. We commissioned an external evaluation of the network in 2017, which affirmed the value of the network, yet identified additional opportunities for growth. We encouraged Alliance members to co-create solutions to address some of the evaluation’s more critical findings. For instance, they identified ways in which they could maximize the benefits of participation while reducing burdensome process. They considered how the Alliance could better equip centers to provide high quality environmental education that is sensitive to community priorities. And they also established clear, measurable goals. With these goals cemented, it became evident that the Alliance members were ready to step up as the primary leaders of the effort, and as a result they formed a steering committee that oversees strategy, budget, governance, membership, and sustainability.

We have also learned a lot about the complexity of collective evaluation as we seek to understand the impact of this network. It is challenging, yet critical, to understand how the centers’ programs and communications affect both who visits their sites and their connections to the watershed. Capacity to do this work is limited across the environmental education field. Our investment in evaluation and learning for the Alliance includes more capacity building for individual centers around data collection and analysis. We have also developed a plan for identifying shared participant outcomes, and standardized ways for collecting data related to those outcomes.

Looking Ahead

With a new steering committee in place driving strategy, the Alliance’s work will continue to evolve, including a stronger emphasis on diversity, equity, inclusion, and access through a dedicated working group, as well as a heightened focus on measurement and evaluation.

To that end, we have committed funding for a market research project that will help the Alliance better understand how local audiences use the centers and rivers, as well as their attitudes about the role and value they both provide to the community. This research will be made available to centers so they can use it to continue to improve the ways they reach people.

Visit www.watershedalliance.org to keep up with the Alliance’s work.

Interested in learning more about our funding of the Alliance? Contact Michele Perch at mperch@williampennfoundation.org.

Progress Timeline

More Watershed Protection Stories

The Circuit Trails

Learn More